It could be the mantra of cultural chameleons:

When in Rome, do as the Romans do.

It’s so well known that all you have to do is say, “When in Rome . . .” and we fill in the rest. But where did the phrase come from? Why Rome? And what is it that we should do when we’re there? To find that out, we have to go all the way back to the fourth century—and delve into the practices of the early church.

When Casulanus wrote a letter to Augustine asking “whether it is lawful to fast on the seventh day of the week,” the early church father replied with his “Letter 36,” written in 396 AD. The passage below is Chapter 14 of that letter:

Since, therefore (as I have said above), we do not find in the Gospels or in the apostolical writings, belonging properly to the revelation of the New Testament, that any law was laid down as to fasts to be observed on particular days; and since this is consequently one of many things, difficult to enumerate, which make up a variety in the robe of the King’s daughter, that is to say, of the Church,—I will tell you the answer given to my questions on this subject by the venerable Ambrose Bishop of Milan, by whom I was baptized. When my mother was with me in that city, I, as being only a catechumen, felt no concern about these questions; but it was to her a question causing anxiety, whether she ought, after the custom of our own town, to fast on the Saturday, or, after the custom of the Church of Milan, not to fast. To deliver her from perplexity, I put the question to the man of God whom I have just named. He answered, “What else can I recommend to others than what I do myself?” When I thought that by this he intended simply to prescribe to us that we should take food on Saturdays—for I knew this to be his own practice—he, following me, added these words: “When I am here I do not fast on Saturday; but when I am at Rome I do: whatever church you may come to, conform to its custom, if you would avoid either receiving or giving offence.” This reply I reported to my mother, and it satisfied her, so that she scrupled not to comply with it; and I have myself followed the same rule. Since, however, it happens, especially in Africa, that one church, or the churches within the same district, may have some members who fast and others who do not fast on the seventh day, it seems to me best to adopt in each congregation the custom of those to whom authority in its government has been committed. Wherefore, if you are quite willing to follow my advice, especially because in regard to this matter I have spoken at greater length than was necessary, do not in this resist your own bishop, but follow his practice without scruple or debate.

Augustine, “Letter 36,” to Casulanus, Chapter 14, 396 AD, in Philip Schaff, ed., Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series I, Volume I, J.G. Cunningham, translator, Christian Literature Company, 1892

Thus, the ultimate source of “When in Rome” is Ambrose, quoted by Augustine, speaking on whether or not to fast on Saturday.

A few years later Augustine returned to the story of his mother and Ambrose in his reply to Januarius, who had posed these questions concerning taking communion (“the sacrifice”) during Lent:

What ought to be done on the Thursday of the last week of Lent? Ought we to offer the sacrifice in the morning, and again after supper, on account of the words in the Gospel, “Likewise also . . . after supper”?

Augustine replied that some practices in the church are authorized by Scripture, and some are set by traditions followed by the global church. But in a third category, there is room for freedom:

There are other things, however, which are different in different places and countries: e.g., some fast on Saturday, others do not; some partake daily of the body and blood of Christ, others receive it on stated days: in some places no day passes without the sacrifice being offered; in others it is only on Saturday and the Lord’s day, or it may be only on the Lord’s day. In regard to these and all other variable observances which may be met anywhere, one is at liberty to comply with them or not as he chooses; and there is no better rule for the wise and serious Christian in this matter, than to conform to the practice which he finds prevailing in the Church to which it may be his lot to come. For such a custom, if it is clearly not contrary to the faith nor to sound morality, is to be held as a thing indifferent, and ought to be observed for the sake of fellowship with those among whom we live.

I think you may have heard me relate before, what I will nevertheless now mention. When my mother followed me to Milan, she found the Church there not fasting on Saturday. She began to be troubled, and to hesitate as to what she should do; upon which I, though not taking a personal interest then in such things, applied on her behalf to Ambrose, of most blessed memory, for his advice. He answered that he could not teach me anything but what he himself practised, because if he knew any better rule, he would observe it himself. When I supposed that he intended, on the ground of his authority alone, and without supporting it by any argument, to recommend us to give up fasting on Saturday, he followed me, and said: “When I visit Rome, I fast on Saturday; when I am here, I do not fast. On the same principle, do you observe the custom prevailing in whatever Church you come to, if you desire neither to give offence by your conduct, nor to find cause of offence in another’s.” When I reported this to my mother, she accepted it gladly; and for myself, after frequently reconsidering his decision, I have always esteemed it as if I had received it by an oracle from heaven. For often have I perceived, with extreme sorrow, many disquietudes caused to weak brethren by the contentious pertinacity or superstitious vacillation of some who, in matters of this kind, which do not admit of final decision by the authority of Holy Scripture, or by the tradition of the universal Church or by their manifest good influence on manners raise questions, it may be, from some crotchet of their own, or from attachment to the custom followed in one’s own country, or from preference for that which one has seen abroad, supposing that wisdom is increased in proportion to the distance to which men travel from home, and agitate these questions with such keenness, that they think all is wrong except what they do themselves.

The above section is Chapter 2 of Augustine’s “Letter 54,” written in 400 AD. In the letter’s Chapter 4, he furthers his argument, not only saying it is inappropriate to take one’s customs into a new setting, but he also cautions against returning home with customs learned abroad and, acting the part of the enlightened traveler, promoting them as superior:

Suppose some foreigner visit a place in which during Lent it is customary to abstain from the use of the bath, and to continue fasting on Thursday. “I will not fast today,” he says. The reason being asked, he says, “Such is not the custom in my own country.” Is not he, by such conduct, attempting to assert the superiority of his custom over theirs? For he cannot quote a decisive passage on the subject from the Book of God; nor can he prove his opinion to be right by the unanimous voice of the universal Church, wherever spread abroad; nor can he demonstrate that they act contrary to the faith, and he according to it, or that they are doing what is prejudicial to sound morality, and he is defending its interests. Those men injure their own tranquillity and peace by quarrelling on an unnecessary question. I would rather recommend that, in matters of this kind, each man should, when sojourning in a country in which he finds a custom different from his own consent to do as others do. If, on the other hand, a Christian, when travelling abroad in some region where the people of God are more numerous, and more easily assembled together, and more zealous in religion, has seen, e.g., the sacrifice twice offered, both morning and evening, on the Thursday of the last week in Lent, and therefore, on his coming back to his own country, where it is offered only at the close of the day, protests against this as wrong and unlawful, because he has himself seen another custom in another land, this would show a childish weakness of judgment against which we should guard ourselves, and which we must bear with in others, but correct in all who are under our influence.

Augustine, “Letter 54,” to Januarius, 400 AD, in Philip Schaff, ed., Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series I, Volume I, J.G. Cunningham, translator, Christian Literature Company, 1892

This English translation of Chapter 4 includes a summary of Ambrose’s advice that gets closer to the wording of our present-day “When in Rome”:

[E]ach man should, when sojourning in a country in which he finds a custom different from his own consent to do as others do.

Many years later, in 1599, the English playwright Henry Porter wrote The Pleasant History of the Two Angry Women of Abington. In it, one of the characters, Nicholas Proverbs, says,

Nay, I hope, as I have temperance to forbeare drinke, so have I patience to endure drinke: Ile do as company doth; for when a man doth to Rome come, he must do as there is done.

Henry Porter, The Pleasant History of the Two Angry Women of Abington, 1599, in Charles Mills Gayley and Alwin Thaler, Representative English Comedies: From the Beginnings to Shakespeare, Macmillan, 1903

And finally, in 1754, Pope Clement XIV wrote “Letter 44” to Dom Galliard, concerning the monks under his authority. The English translation that followed in 1777 gives us a form of “When in Rome” that brings us nearly to what we have today. This time the topic is the suitability of taking a nap during the day:

The siesto, or afternoon’s nap of Italy, my most dear and reverend Father, would not have alarmed you so much, if you had recollected, that when we are at Rome, we should do as the Romans do.—Cum Romano Romanus eris.

Is it either sin or shame, then, for a poor Monk, in a country where one is oppressed with excessive heat, to indulge in half an hour’s repose, that he may afterwards pursue his exercises with the more activity? Consider, that silence is best kept when one is asleep. You who reckon among the capital sins, the pronouncing of a single word when your rules forbid the use of speech,—take the example of Christ when he found his Apostles asleep: Alas, says he to them, with the greatest mildness, could you not watch with me one hour?

Clement, “Letter 44,” Interesting Letters of Pope Clement XIV (Ganganelli): To Which Are Prefixed, Anecdotes of His Life, Volume I, translated from the French, London, 1777.

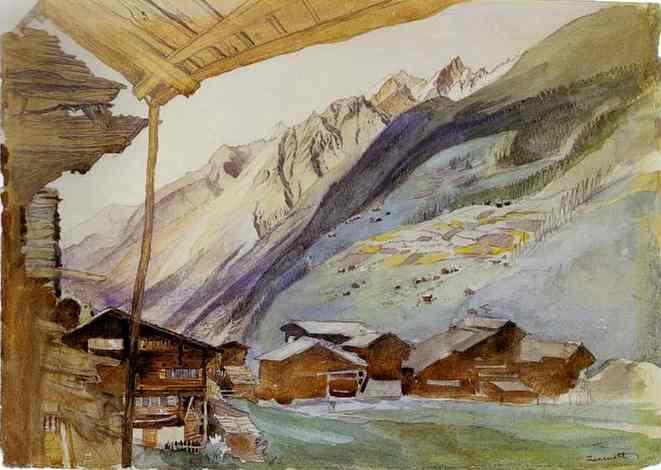

Now that I’ve come to the end of my post, I’ve got to give credit where credit is due. Thanks to The Phrase Finder for identifying most of the sources above. And the photo, titled “Rome,” is by Luca Sartoni (used under a Creative Commons license). There’s some pretty nice architecture in the picture, behind the tourists. I’m thinking it took more than a day to build a place like that. By the way, that area is called Campo Marzio. If you’d like to see it in person, it should be pretty easy to find. I’m guessing that once you’re in Italy, all roads will lead there. And when you arrive, you’ll know what to do.